A University of Melbourne expert covers findings from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey.

Measuring the material factors of our lives — like finances, work, health — can tell us a lot about the state of Australian society, but what matters most to us?

To help answer this question, we need to know not just what people have and don’t have, but how they feel — what researchers call subjective well-being.

The Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey asks these questions of around 17,000 Australians every year. The latest report, released today, shows that over almost two decades (2001-2018), Australians’ life satisfaction has been fairly constant at relatively high levels, driven by basic factors such as health, safety and social contact.

But there are gaps. Unemployed people, immigrants from non-English speaking countries and Indigenous Australians generally all fare worse than other Australians.

Combined with the reduced satisfaction that comes from unemployment, the data is a warning the economic and social cost of controlling the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to have significantly hurt many Australians’ sense of well-being.

The youngest and oldest have the highest life satisfaction

Life satisfaction, as one measure of subjective well-being, is measured in HILDA by asking Australians

All things considered, how satisfied are you with your life overall?

Responses range from 0 to 10 — the higher this score, the more satisfied a person is with their life as a whole.

Respondents were also asked to rate their satisfaction with different areas or domains of life, namely job, finances, housing, safety, leisure, and health.

Australians are generally quite satisfied with their lives. In 2018, for example, the average life satisfaction score was about 7.92 on the 0-10 scale.

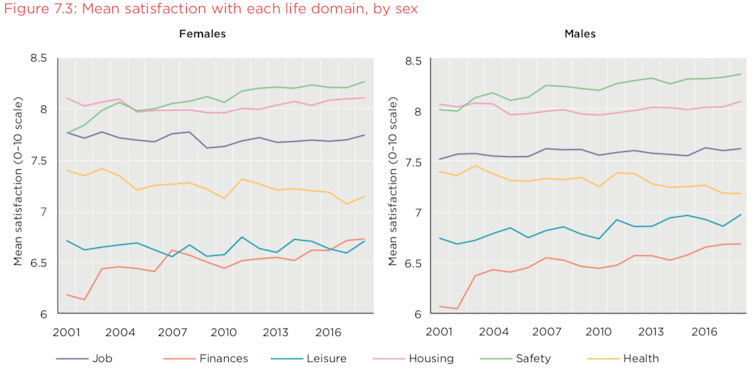

Women report consistently higher levels of life satisfaction compared to men (though this difference is very small), and this has remained consistent over the 18 years of HILDA. But women are less satisfied with leisure time than men, which may reflect the greater child caring burden on women.

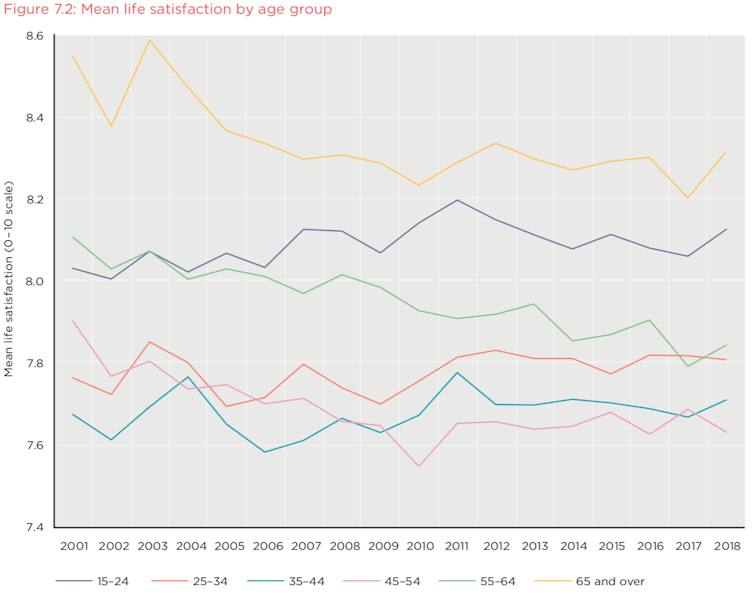

There are also some age differences. As is common across the world, the youngest (15-24) and oldest (65 and over) have the highest life satisfaction, whereas Australians in the 35-44 and 45-54 age groups are consistently the least satisfied with their lives.

The HILDA results confirm a so-called “U-shape” relationship between age and life satisfaction, implying that life satisfaction is relatively high at younger ages, declines during middle age, and starts increasing again at a later stage.

Health and safety: good for most but not all

Health, unsurprisingly, seems to play an important role. People in poor general or mental health, and those with a disability, have substantially lower average life satisfaction than those without such health problems.

As might be expected, employed people have much lower satisfaction with their leisure time than those who are unemployed or not in the labour force. But regardless of gender, unemployed people are much less satisfied with life.

Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians overall reported similar levels of life satisfaction in 2018, but there are relatively large differences in some important domains that suggests Indigenous Australians do worse.

Compared to non-Indigenous people, Indigenous Australians report lower satisfaction with finances, housing, and health.

Apart from health satisfaction, immigrants from non-English speaking countries report lower average well-being in all domains (including with life overall).

When we consider satisfaction in different life domains, Australian men and women are least satisfied with their finances, although financial satisfaction has been increasing somewhat over time.

Australians are most satisfied with their personal safety, and here as well safety satisfaction has exhibited an upward trend over time. Of note is that Australians’ satisfaction with health, although relatively high, has been on a slight downward trend over the past two decades.

Life satisfaction

Married people are more satisfied than those in other marital statuses. One interesting exception, however, is among women in de facto relationships, who are slightly more satisfied with life than married women.

Somewhat counter-intuitively, higher levels of education are related to lower reported life satisfaction. One possible explanation is the hypothesis that more educated persons have higher aspirations which, if not met, may have a detrimental effect on well-being.

Having children is associated with greater life satisfaction for men, but for women there is no relationship between children and life satisfaction. Again, this may in part reflect greater childcare responsibility and is also consistent with women’s lower leisure satisfaction.

People with a disability are especially more likely to report lower life satisfaction.

Having regular social contact and social relationships leads to higher life satisfaction for both men and women, underscoring the importance of maintaining social ties.

The social restrictions imposed to control COVID-19 this year therefore likely had a detrimental effect on the well-being of many Australians, especially in Melbourne.

For both women and men, having higher household income is related to greater life satisfaction, but the effect is pretty small. So, life satisfaction is not just about money.

For women there is no relationship between region of residence and life satisfaction, but men living in major urban areas are much less satisfied with life compared to men living in non-urban areas.

For all Australians, regardless of age or gender, changes in health satisfaction lead to the largest changes in life satisfaction.

After health satisfaction, people’s satisfaction with personal safety is also associated with large increases in overall life satisfaction.

These findings imply basic needs such as being healthy and feeling safe are some of the most important contributors to overall well-being.

What policies and services do we need?

For the most part, the average Australian is doing very well. Overall life satisfaction is generally high, and satisfaction with safety and housing rank among the highest scored domain satisfactions, suggesting most Australians are very satisfied with the provision of their basic needs.

But it is clear the unemployed have very low levels of well-being in most life domains. Subjective well-being is also quite low among immigrants from non-English speaking countries, as well as among Indigenous Australians.

These observations stress the importance of a strong emphasis on factors like job creation and skills development for unemployed people, additional support for immigrants and continued emphasis on Indigenous well-being.

Because health satisfaction is the strongest predictor of overall life satisfaction in Australia, improvements in individual health circumstances are likely to filter through into greater overall life satisfaction.

Finally, the data on Australians suffering from poor health — physical, mental, and those with a disability — signal that the efficient and effective provision of health services to those most in need is paramount.

This piece was co-published with the University of Melbourne’s Pursuit.

![]()

Ferdi Botha, Research Fellow, University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. View the original article. This article reflects the views of the author. Re-published articles do not necessarily reflect the views of the Commission, but are shared here to promote and raise awareness of the complex nature of issues surrounding mental health, alcohol and other drug use, and suicide.